Share Extension Auth in iOS 18: Four Approaches Compared

For years, the Share icon on mobile was just visual noise to me — something that kept appearing everywhere but I never used. Then something clicked: Share is like a Unix pipe. You take content from one app and send it to another in one action. No copy-paste, no saving files, no searching for “import” — just pick the next tool and continue the chain. The only difference is that instead of a stream, Share passes a package (a link, text, a file, or several photos).

The problem is that Unix pipes live inside a single user environment, while Share crosses app boundaries: separate sandboxes, separate processes, separate security rules. So the task “pass data” quickly becomes “pass data in the user’s context”: the receiver needs to know who the current user is and where to put this package. In my case: a user shares a link to my app, but processing happens on the server, so the user needs to be authenticated first. What do you do when a Share request arrives but there’s no session — or the session isn’t available right now?

The naive solution: “just open the app”

The first idea that comes to mind: the extension detects that the user is not logged in and opens the main app. The user logs in, goes back to Safari, taps Share again — and now everything works.

In code, it looks simple:

extensionContext?.open(URL(string: "dropkind://login")!) { success in

self.extensionContext?.completeRequest(returningItems: nil)

}

Or via Universal Links:

extensionContext?.open(URL(string: "https://dropkind.app/auth")!)

This pattern worked for years. Share Extension acted as a launcher: it detected a problem, passed control to the main app, and closed.

In iOS 18, this stopped working.

What Apple broke (and why it’s not a bug)

When you try to open an app from a Share Extension in iOS 18, you get an error:

LSApplicationWorkspaceErrorDomain Code=115

This is not a bug or a temporary regression. Apple explicitly states that app extensions are not allowed to open URLs directly; runtime workarounds are being blocked. If you need the user’s attention — use a local notification.

Cold start / Warm start

In my experience, extensionContext.open(...) sometimes works when the app is already in memory — but you can’t control or predict that, and it’s not documented. The user might have closed the app an hour ago, and the call will silently fail.

What Apple recommends instead of openURL

On the same forum, Quinn writes:

“If your app extension needs to get the user’s attention, do that by posting a local notification.”

The idea is that an extension should not be a trampoline to the main app — it should handle the task on its own. If it can’t — it should just tell the user via a local notification.

Old hacks no longer work

If you googled this problem before, you probably saw the UIResponder chain “hack”:

// THIS NO LONGER WORKS

var responder: UIResponder? = self

while responder != nil {

if let application = responder as? UIApplication {

application.perform(#selector(openURL(_:)), with: url)

break

}

responder = responder?.next

}

Starting with iOS 18, this code throws a sandbox error (NSOSStatusErrorDomain Code=-54). The system checks the call stack and blocks attempts to bypass restrictions.

How Apple’s own apps do it

It’s interesting to see how Apple solves this problem in their own apps. Here’s what I found:

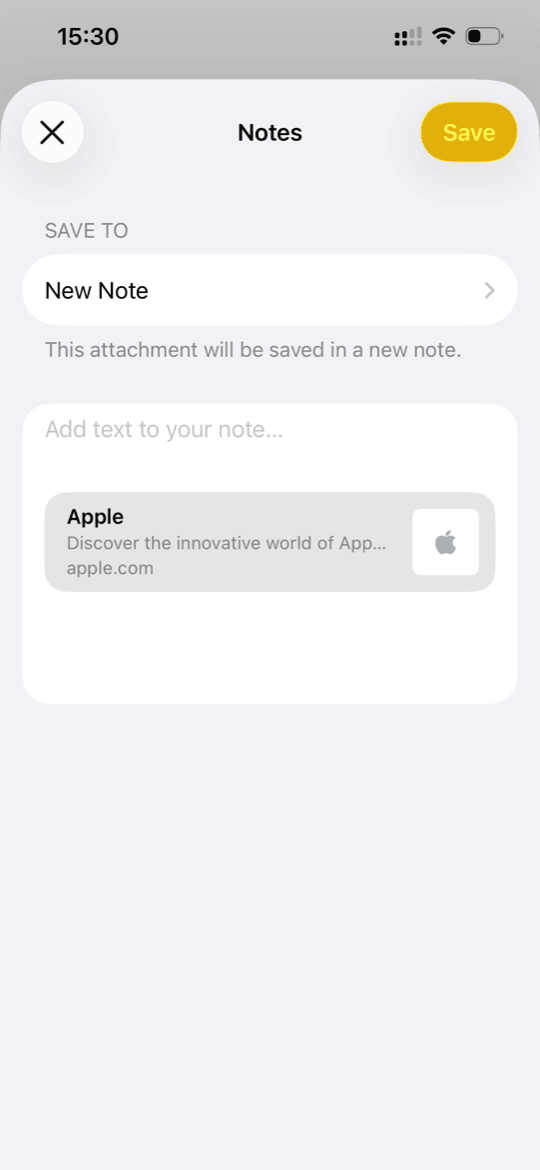

Notes: when sharing a link to Notes, the extension shows a folder picker, you tap “Save” and… you stay in Safari. The note is saved via background sync, and you only find out when you open Notes.

Photos: same approach — the extension saves to a shared container, sync happens in the background.

Messages: if you select a contact from “suggestions” in the Share Sheet, the system itself opens Messages. This is a system-level path, not openURL from an extension.

So Apple’s apps either don’t open the main app at all, or they use privileged system mechanisms that are not available to third-party developers.

Working solutions

Solution A: Shared Keychain — the extension handles auth on its own

The best solution is to make the extension autonomous. If the extension has access to the auth token, it can send data to the server by itself, without touching the main app.

The idea is simple: the main app saves the token to Keychain with a shared access group when the user logs in, and the Share Extension reads it and makes the API request itself.

// In the main app during login:

let query: [String: Any] = [

kSecClass as String: kSecClassGenericPassword,

kSecAttrAccount as String: "authToken",

kSecAttrAccessGroup as String: "group.com.dropkind.shared",

kSecValueData as String: token.data(using: .utf8)!

]

SecItemAdd(query as CFDictionary, nil)

// In Share Extension:

let query: [String: Any] = [

kSecClass as String: kSecClassGenericPassword,

kSecAttrAccount as String: "authToken",

kSecAttrAccessGroup as String: "group.com.dropkind.shared",

kSecReturnData as String: true

]

var result: AnyObject?

SecItemCopyMatching(query as CFDictionary, &result)

The main advantage is perfect UX: the user taps “Save” and stays where they were. You just need to set up Keychain Sharing between targets and make sure the token is available (not expired, not revoked).

Important detail: Keychain can survive app deletion, so you can’t rely on automatic cleanup. Imagine this scenario: a user logged in, deleted the app, created a new account a year later (for example, in the web version of your service), installed the app, and immediately used Share — the extension would find the old token and send data to the wrong user.

The fix: App Group UserDefaults, unlike Keychain, gets deleted with the app. Store currentUserId in UserDefaults and check for it before using the token:

// In Share Extension:

let shared = UserDefaults(suiteName: "group.com.dropkind.shared")

guard shared?.string(forKey: "currentUserId") != nil else {

// UserDefaults is empty → app was reinstalled → require login

return

}

// Only now trust the token from Keychain

Solution B: App entry via local notification

If the extension can’t open the app programmatically, let the user do it by tapping a local notification:

- Extension detects there’s no session

- Saves data to temporary storage (App Group UserDefaults)

- Shows a local notification: “Tap to log in and save the link”

- User taps — this is a legitimate action, the system allows the app to launch

// In Share Extension:

func showLoginNotification(pendingURL: URL) {

// Save data

let defaults = UserDefaults(suiteName: "group.com.dropkind.shared")

defaults?.set(pendingURL.absoluteString, forKey: "pendingShare")

// Schedule notification

let content = UNMutableNotificationContent()

content.title = "Login required"

content.body = "Tap to log in to DropKind and save your link"

content.userInfo = ["action": "completeShare"]

let request = UNNotificationRequest(

identifier: "loginRequired",

content: content,

trigger: nil // Show immediately

)

UNUserNotificationCenter.current().add(request)

}

The implementation is simple and works reliably. The downside is an extra step for the user, and you need notification permission.

In practice: robust API, flaky UX

I tried this approach and found it unreliable in practice:

- Users deny notification permission reflexively

- Focus Mode / Do Not Disturb suppresses notifications silently

- Even delivered notifications get dismissed without reading

- Too many steps between “tap Share” and “complete the action”

Local notifications are robust from iOS’s standpoint — Apple recommends it, the API is stable and documented. But they’re flaky from a UX standpoint. Too many points of failure for the user to actually complete the share.

Solution C: OAuth inside the extension

The most complex option: implement full OAuth login right in the Share Extension using ASWebAuthenticationSession. The user authenticates without leaving the Share Sheet, the token is saved to Shared Keychain, and future shares work autonomously.

The UX is seamless — but the implementation is a lot of work. Not all OAuth providers play nice with extensions, and ASWebAuthenticationSession has quirks when running outside the main app context.

Solution D: UIWindowScene.open() via responder chain

Remember the old UIResponder chain hack that Apple blocked? It turns out there’s a variation that still works on iOS 18+. Instead of walking up to UIApplication, you walk up to UIWindowScene and call its open(_:options:completionHandler:) method:

static func openViaResponderChain(

from viewController: UIViewController,

url: URL,

completion: ((Bool) -> Void)? = nil

) {

var responder: UIResponder? = viewController

while let current = responder {

if let scene = current as? UIWindowScene {

scene.open(url, options: nil) { success in

completion?(success)

}

return

}

responder = current.next

}

completion?(false)

}

This works because UIWindowScene.open() isn’t subject to the same restrictions as UIApplication.open(). The system doesn’t block it — at least not yet.

Caveat: This is undocumented behavior. Apple could block it in a future iOS version, just like they blocked the UIApplication approach. Always have a fallback ready.

What I chose

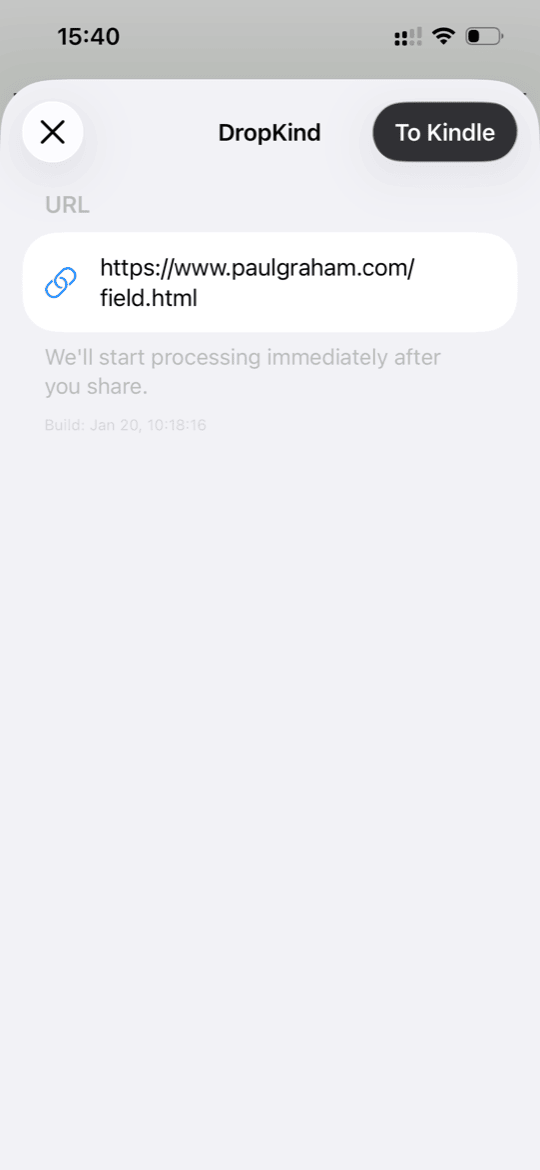

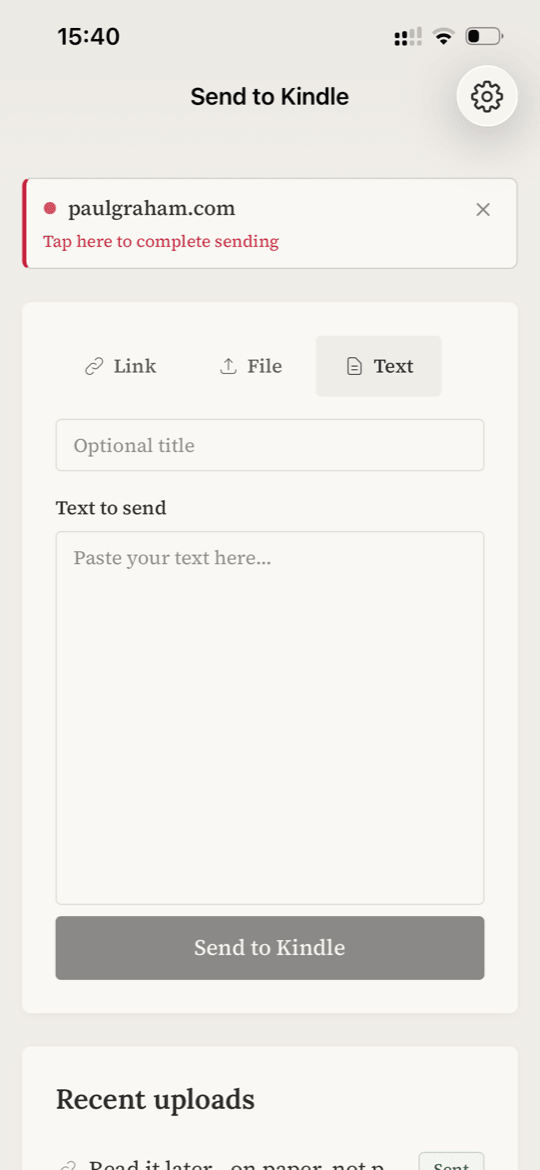

DropKind is a simple app that sends articles and text to your Kindle. You find something interesting while browsing — share it to DropKind, and it lands on your e-reader. The Share Extension is the main entry point: most users discover content in Safari, not in the app itself. So a broken or clunky share flow means a broken product.

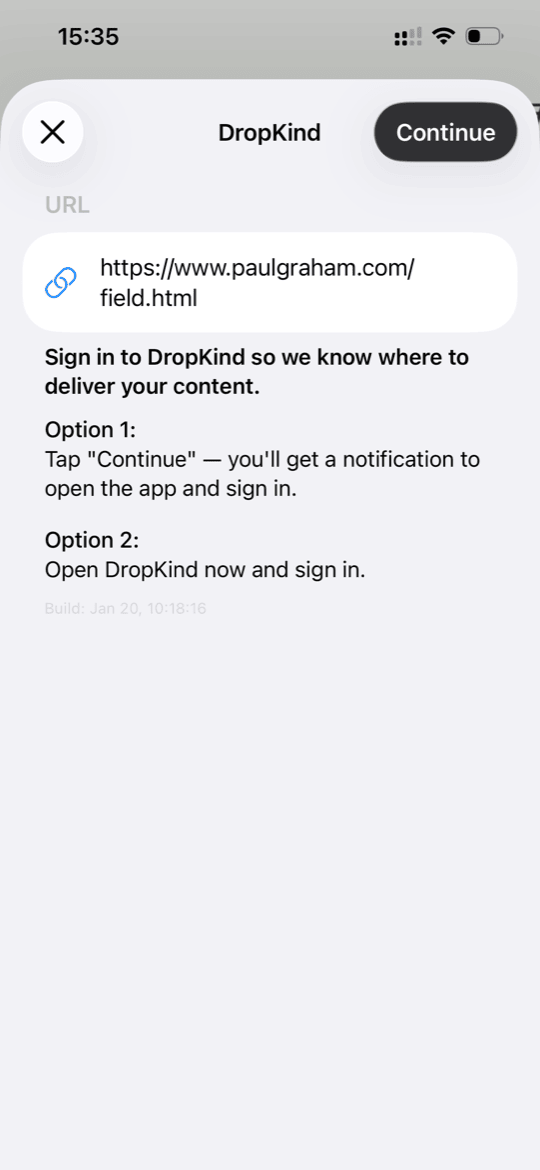

For DropKind, I chose a combination of solutions A and D, with a manual fallback. The main path is Shared Keychain: if the user is already logged in to the app, the extension picks up the token and works autonomously. If there’s no token — we try to open the app via UIWindowScene, and if that fails, we show an in-extension prompt.

Implementation details:

1) Separate share-token in Keychain. The main app gets a separate share-token and saves it to Shared Keychain. Share Extension uses this token for direct POST to the API.

2) user_id in App Group. Along with the token, we save user_id to App Group UserDefaults. This serves two purposes: the server verifies the token owner, and the presence of user_id itself is a marker that the app wasn’t reinstalled (UserDefaults gets deleted on uninstall, unlike Keychain).

3) If there’s no token — the extension saves data to App Group and attempts UIWindowScene.open() via the responder chain. This has worked reliably for me on iOS 18.

4) If UIWindowScene.open() fails — the extension shows an in-extension prompt asking the user to open the app manually. This is the final fallback, no notifications involved.

5) The main app finishes the job. On launch, the app checks for pending share data in the App Group, guides the user through login if needed, and completes the share.

This approach gives the best UX for most users (those already logged in), but doesn’t break for new users.

Going back to the pipe analogy: grep doesn’t ask you to configure anything — it just works with what it has. A Share Extension should aim for the same, handling auth silently whenever possible.